Sorcerer (1977)

Not pictured: A sorcerer.

This might be hard to imagine now, but there was once a magical time called “The 1970s”. It began as an age of luxuriant body hair, giant cars festooned with miles of chrome, and ended in an avalanche of earth tones in corduroy and polyester.

It was also the era of visionary mad scientist directors like William Friedkin, used to being given carte blanche by studios eager to utilize his genius. By 1977, the director of The French Connection and The Exorcist could do whatever the hell he wanted.

But the 1970s were also still a time where Actors with a Capital A still roamed the earth, bestowed by their catalogue with the clout to associate themselves with only the most challenging projects. Roy Scheider was such a man, having made his name in thinkers like Klute and alongside Friedkin himself in The French Connection.

Scheider’s most recent film had been a little thing called Jaws, but you’ve probably never seen that. The two giants joined forces again for Sorcerer, the bleak, jaw-dropping epic Friedkin had hoped would be his masterpiece.

And you know something? I think maybe it IS.

The film’s first act is divided into four parts, each longer and more intense than the last. Each establishes the already in-progress arc of our main characters.

You’ll notice I didn’t say “heroes”.

Nilo (Francisco Rabal) is an international hit man facing serious blowback from his most recent contract. Kassem (Amidou) is a Palestinian militant who just blew up a large chunk of Jerusalem. Victor (Bruno Cremer) is a French investment banker who invested a little too much of his clients’ money in himself.

And Jackie (Scheider) is a New Jersey mobster whose gang just knocked over the wrong racket. Having incurred the wrath of the city’s most vengeful crime lord, Jackie accepts a one way plane ticket to the farthest possible corner of the planet.

He eventually finds himself in Columbia. Specifically, at an airfield alongside a sleepy mountain village that from above, looks like a puddle of mud filled with broken popsicle sticks.

Don’t feel bad. These are not good people.

Rocking that hat in the jungle adds points, though.

In fact, they’re all very bad people. And they’re marked for death by the kind of people bad people run from.

There’s a single oil rig outside the village, keeping the community clinging to life with ample jobs, but meager wages. The village police are predictably corrupt, living conditions for all concerned can be charitably described as “wretched” and every third inhabitant is filled with latent murderous rage at all the above.

It’s also an open secret that things could be better if not for both the fascist local government and their American overlords skimming profits off the top. The place is a powder keg, and into this muddy hellhole land four desperate criminals who haven’t lost their taste for wealth, freedom or whatever potential virtue they’ve habitually turned into vice.

A way out appears when insurgents sabotage the well, setting it on fire.The attack kills dozens and threatens the very existence of the town. The only way to stop the fire is to blast it with dynamite, but the nearest supply is 200 miles away. And, it’s been sitting so long that it’s dangerously degraded.

The slightest impact could set it all off.

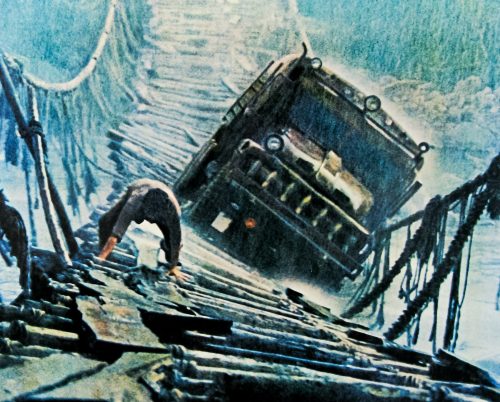

After a series of false starts two heavily modified trucks are chosen, with a pair drivers each. It’s an exceedingly treacherous journey over rain slicked terrain in a pair of rickety vehicles filled with unstable explosives. Each man agrees to the task because, as we’ve seen, life in this part of the world is a fate much worse than death.

But you do get to drive this.

Up to this point Sorcerer has given us an hour of setup, with mostly subtitled non-English dialog. The world building that unfolds after we reach the village is almost exhausting to watch. But it establishes, without subtlety, the desperately grim nature of life there.

It’s ghastly and riveting all at once. The relentless montage of human suffering is only occasionally punctuated by terse, expository dialog, police corruption and shocking vistas of raw brutality. At times, you’re not sure you aren’t watching an uncompromising documentary or worse, a snuff film.

But I can tell you that by the time our drivers agree to risk almost guaranteed death for the chance to leave this place, you fully accept it. These are men used to living life at a certain level of entitlement. They can’t quite let go of the appetites that chased them here, so they flee into the beautiful, yawning darkness of the jungle.

To suddenly be required to live in absolute squalor is a bridge too far.

What follows is not only a literal bridge, but a moral exercise worthy of Heart of Darkness, or The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. The lengths to which people will go, and the depth to which we’re often willing to sink – all to avoid facing the consequences of our own choices – is nothing short of intimidating.

We watch a quartet of terrible people overcome incredible obstacles against withering odds. They briefly join forces to display uncommon bravery only to be reminded, along with the viewer, that nothing is more permanent than nature.

Except, perhaps, man’s own inhumanity to man.

The only thing more alarming might be the levels of ego and hubris that went into creating this implacable meditation on human brutality.

Nearly everyone of note involved with the production is on record calling this the most difficult shoot of their career. Freidkin, along with most of the crew, required hospitalization at one time or another. Scheider may have suffered some sort of permanent emotional damage. The budget ballooned from two to twenty two million dollars.

The director was obsessed. One cinematographer got fed up halfway through filming and was replaced with another. But by God, every penny spent and every ounce of blood, sweat and tears shed is up on that screen.

All of it.

This is not a film to be watched so much as it is an experience that must be endured. If you enjoy films that wring emotional responses from you and leave you lost in thought for hours afterward, then step right up.

Two more things.

One, the film’s soundtrack is by pioneering electronic group Tangerine Dream. It’s reminiscent of (and arguably superior to) a John Carpenter score; deceptively simple but organically crucial to the story.

And two…

Why the hell is this movie called Sorcerer?!?

The film itself is the second adaptation of the novel The Wages of Fear, the first having been a well regarded classic back in the 1950s. Friedkin made some changes to the story and one of them involved naming the vehicles. One of the trucks (guess which) is called Sorcerer, which is fine.

But it’s never highlighted in the movie, much less presented as a plot point. Sorcerer is also just a terrible name for a film where the hero is not a wizard (or even a hero) and the story is all about trucks and death and (actual term) “sweaty dynamite” .

Pictured: Sweaty Dynamite.

Just forget all that, though. For anyone who just loves storytelling, this is essential viewing. Even if I didn’t love this movie, and I do, I’d be willing to recommend it because it deserves to be experienced.

Sorcerer is only two hours long but it takes at least three out of you. It’s a story all about the illusion that any of us are in control of our own fate. And in that spirit I say make it a challenge, and watch it while drinking something you’re not sure you enjoy.

Like it or not, you’ll never forget it.

Categories

Bruce Hall View All

“When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favorite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol' Bruce Hall always says at a time like that: "Have ya paid your dues, Bruce?" "Yes sir, the check is in the mail."

Outstanding review, Bruce. I knew Sorcerer was one you would appreciate when you finally got around to watching. But I’m gratified it has the same inexplicable hold on you that it has on me.