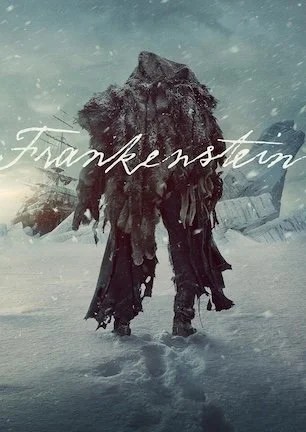

Frankenstein (2025)

Not your father’s Frankenstein. Or, his father’s. Or, even HIS…

Imagine my skepticism when I first heard that Netflix, of all people, would attempt to re-imagine Mary Shelley’s classic 1818 novel Frankenstein. Most people are familiar with the basic scaffolding of the story: a brilliant scientist assembles a living being from remnants of the dead, and the results prove disastrous for everyone involved.

The problem is, there are a lot of ways to tell that story.

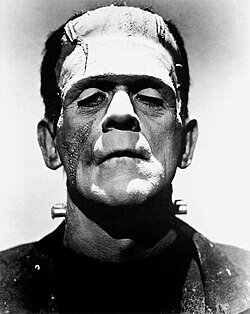

For two centuries, audiences have been trained to picture “Frankenstein” as a raving madman and his creation as a bolt-necked brute—a gothic spectacle of thunder, terror, and punishment for hubris. That image, cemented by James Whale’s venerable 1931 film and calcified by pop culture ever since, eventually turned Shelley’s intimate tragedy into a morality play about the dangers of “playing God.”

Not to say that’s wrong. Shelley’s original tale does have plenty to say about what happens when the act of making life isn’t matched by the capacity to love it.

But the book isn’t really about science gone too far.

It’s about love gone missing. The original Victor Frankenstein was never a cackling mad genius in a castle. He was a frightened man who recoiled from the thing he made the instant it reminded him of himself. His great sin wasn’t ambition; it was abandonment.

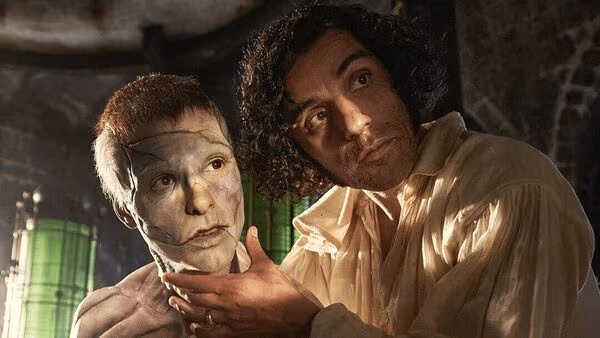

Who could abandon a face like that?

Shelley’s “monster,” conversely, was no brute. He was a newborn intellect, capable of reason and compassion, driven to violence only after relentless rejection.

Whale’s definitive film is only one of many adaptations, with Frankenstein himself often portrayed as a mad genius, a romantic obsessive, or a scientific daredevil. The Creature has been depicted variously as a childlike brute, a sympathetic victim, and even (gah) a superhero figure. The films themselves have ranged in quality from the raw gothic horror of the 1931 classic to Kenneth Branagh’s competent but overcooked Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994) to the preposterous comic-book fantasy I, Frankenstein (2014).

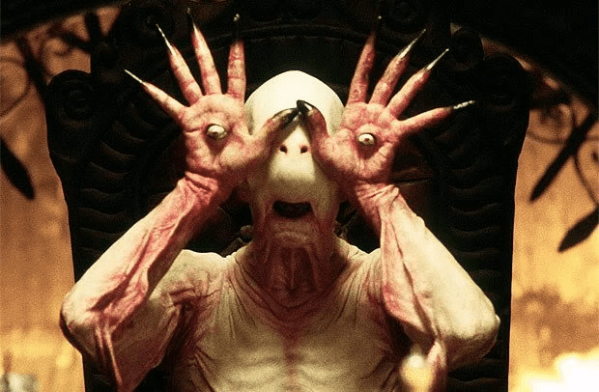

So no, I wasn’t terribly psyched about the idea—until I heard the name behind it: Guillermo del Toro.

From his haunting signature film Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) to his Oscar-winning genre subversion The Shape of Water (2017), del Toro has proven himself a master at examining those who are rejected and misunderstood—often through the language of fantasy and the supernatural. His monsters are never mascots or metaphors of convenience; they are emotional conduits.

Pictured: A conduit.

What I’m getting at is this: Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein doesn’t re-imagine Mary Shelley’s story so much as resurrect it—from decades of misinterpretation, parody, and cultural shorthand. Shelley’s original moral geometry is clear: creation without acceptance of moral responsibility is the true horror.

Del Toro restores that symmetry.

His Frankenstein feels less like a horror movie and more like a confessional, reckoning with the most appalling parental failure imaginable: a refusal to see one’s progeny as worthy of compassion. Del Toro’s long-standing preoccupation with misunderstood beings reaches its fullest expression here. In this version of the tale, the Creature isn’t a monster so much as an emotional mirror, reflecting the guilt and cruelty of the man who created him.

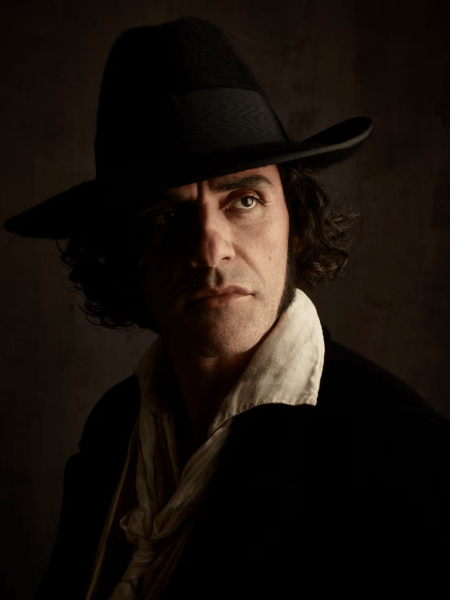

When Victor Frankenstein (Oscar Isaac, delivering a commanding performance) was a child, his father (Charles Dance, delivering a chilling one) treated him less like a son than a science project — something to be perfected rather than understood. This often-violent upbringing instills in Victor a profound sense of inadequacy and resentment, along with the belief that discipline and emotional mastery are more valuable human traits than empathy or compassion.

That’s not to say one can’t still be fashionable…

Victor’s mother (Mia Goth), by contrast, represents his only experience of love untainted by expectation or judgment. Her sudden and tragic death becomes the defining rupture of his life. It plants a question that will never leave him: must death be absolute, or can it be mastered?

From this point forward, Victor’s intellectual brilliance becomes inseparable from grief. His pursuit of science is no longer abstract curiosity; it is an attempt to impose order on loss—to correct what feels to him like a cosmic injustice.

As Victor matures, his fixation on conquering death intensifies. He ultimately succeeds in animating a body assembled from the remains of multiple corpses. But when the Creature (Jacob Elordi) awakens, Victor recoils in horror, unable to reconcile the living being before him with the abstract victory he imagined.

He attempts to communicate with it and eventually fails, unsettled by its fixation on him. So rather than recognizing that attention as affection, Victor panics and abandons the Creature almost immediately, treating it as a failed experiment rather than a sentient person.

I call it…Blue Steel…

Notably, the film doesn’t begin with this backstory. Instead, it opens with a thrilling and oddly poignant action sequence that introduces both Victor and his creation without context, trusting the audience to recognize them on sight. The story then unfolds as an extended flashback, gradually filling in the emotional and moral gaps.

Frankenstein is part chase epic, part gothic horror, part cautionary tale of generational trauma, all laced with the faint mysticism and stubborn humanity that define del Toro’s work. As the story develops, we’re given perspective from both Victor and the Creature, sharpening the tragedy and raising the stakes.

How do Victor’s choices affect his younger brother William (Felix Kammerer) and his winsome fiancée Elizabeth (also Mia Goth)? Spoiler alert: not well. And what of the Creature, whose nightmarish existence begins with the mind of a frightened child, forced to navigate—alone—an increasingly cruel and unforgiving world?

That’s not to say one can’t still be fashionable…

This is a beautiful film, full of surprising emotional turns and breathtaking imagery—shout out to GDT’s BFF cinematographer Dan Laustsen (Nightmare Alley, The Shape of Water). Yet for all its visual grandeur, Frankenstein remains grounded in a grim, persistent moral clarity. Del Toro never lets us forget that this is not a story about the danger of creating life—it’s about the consequences of refusing to care for it.

That this version of Frankenstein arrives via Netflix rather than a traditional studio feels both practical and symbolic. Few studios would bankroll a film this patient, this mournful, or this unwilling to turn its monster into a franchise-ready figure. Netflix’s role here isn’t as tastemaker so much as enabler—allowing del Toro the space to follow Shelley’s tragedy to its most uncomfortable conclusions.

Are Netflix originals the future of cinema? Based on their ratio of garbage to greatness over the last ten years, it’s been hard to get excited. But based on Frankenstein alone, I believe there’s reason for hope.

That might be the greatest resurrection of all.

Categories

Bruce Hall View All

“When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favorite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol' Bruce Hall always says at a time like that: "Have ya paid your dues, Bruce?" "Yes sir, the check is in the mail."