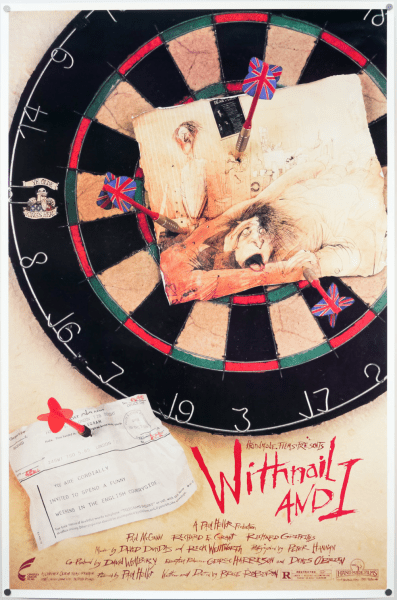

Withnail and I (1987)

Withnail and I is neither the most depressing comedy nor the most hilarious portrait of human disintegration ever put on screen. It lacks both the effervescent charm of Arthur (1981) and the relentless fatalism of Leaving Las Vegas (1995).

Instead, it offers a more uncertain read on its characters, leading us into, through, and beyond an intractable period of life where, for some, personal potential curdles into pointless inertia. Withnail and I will send a thunderbolt of familiarity down the spine of anyone who has ever found themselves still wandering the avenues of youthful rebellion at the dawn of middle age.

Withnail (Richard E. Grant) and Marwood (Paul McGann) are roommates adrift in that uneasy gap between earning a degree and waiting to reap the fruits of having done so. Both are trained actors, which makes their post-college years feel even more urgent. As time passes, they begin to feel the weight of ambition unfulfilled — the inexorable panic of realizing that a life built on youthful passion may have to give way to one built on realism and economic necessity.

Please enjoy this random, unrelated image of a colorful, unnamed animated character.

For Marwood, this culminates the morning after a particularly aggressive night of booze and drugs. The camera observes the disheveled ruins of their apartment — not unlike a helicopter flyover of a war-torn ghetto. The mournful strains of Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale” echo, perhaps diegetically, in the background.

Marwood is having a full-on existential revelation, and the results are mortifying.

Meanwhile, Withnail has fully embraced the starving–but thoroughly inebriated–artist’s lifestyle, cloaking his lack of fulfillment with heavy doses of drugs and debauchery. In contrast to Marwood’s internal hell of self-doubt and recrimination, Withnail is a delusional egoist, trapped within a cycle of perpetual performance.

Where Marwood seems to find gratification in the connection art can build between people, Withnail is driven by the perpetual need for personal validation that never comes. The film is largely told from Marwood’s point of view, occasionally accompanied by his sardonic, self-effacing narration.

His interior voice gives the story its melancholy undercurrent—the distance between what’s funny and what’s true.

About…this much distance.

Writer-director Bruce Robinson wrote Withnail and I out of his years as a struggling actor in the late 1960s. That hint of biographical adjacency might be the special sauce that keeps the tone so unstable. It’s funny, but the humor is too truthful to be mere escapism. The performances are heightened, but the emotions underneath are painfully recognizable. The story constantly teeters between farce and tragedy, keeping you in a state of compassionate unease.

When the Boys decide to take a break from their mutual collapse to enjoy a country vacation — courtesy of Withnail’s rich, eccentric uncle Monty (Richard Griffiths, in a powerfully rangy performance) the story seems ready to tip into farce. Up to this point, their only confirmed associate has been Withnail’s drug dealer, Danny (Ralph Brown), a mildly terrifying oddball who had me laughing and wondering whether this was the kind of movie where the leads might actually die.

When you love to do drugs for a living, you’ll never work a day in your life.

If Withnail and I had chosen one extreme or the other — bawdy comedy or hard-nosed morality play — it might have been memorable only to the handful of people who saw it at the time. Instead, it throws the story back to the audience, reeling us in with excess and outrage but keeping us engaged through sudden flashes of compassion and self-preservation.

You’re never quite certain whether you’re watching a madcap romp or a eulogy in motion — until you are.

Not pictured…certainty.

It’s like tentatively trying a wasabi-flavored M&M and looking up ninety minutes later to find yourself holding an empty bag, hand over your mouth, wistfully — and gravely — contemplating the mysteries of life.

Everyone experiences periods of developmental uncertainty, but few endure them under the weight of artistic ambition. Anyone who has a favorite movie, song, or book must realize that these works of art are crafted by people whose worldview might feel alien to most of society. Perhaps that’s what it is to be truly creative.

Of course, not everyone can relate to the emotional nakedness and performative lifestyle that come with the acting profession.

Still, most of us can recall a formative moment when the future felt murky — when we pulled over to the side of the proverbial road to question our life choices. We learn that success doesn’t always look like what we envision. Failure isn’t an ending, but a new beginning. And sometimes, the people you think are your friends are just assholes.

Occasionally, they’re even the whole ass.

Some call it “growing up.” Others call it “maturation.” My high school football coach referred to it as “getting your shit together.”

The point is, we either make the choice to fully step into adulthood—compromise, responsibility, and survival—or we don’t.

Marwood, when we meet him, is beginning to question whether there’s at least a more practical way to satisfy his creative drive and still survive as a functioning adult. Withnail, on the other hand, clings to theatrical bravado because he senses the world will never recognize him as extraordinary. Watching the two of them drag their poisonous lives into the country and try to survive—without drugs—serves as a hilarious entry point into the true meat of the story, which, I admit, I was unprepared for.

It’s a beautiful sleight of hand that, if you’re mentally prepared to meet it where it is, will linger with you indefinitely. Fun side note: this was my first time seeing Withnail and I, which was released in 1987.

What took so long? Everyone who’s ever begged me to watch it has been an actor — and they always sound like Withnail when they describe it.

Withnail and I is a cinematic blessing — and an ironic curse — that just keeps on giving.

Categories

Bruce Hall View All

“When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favorite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol' Bruce Hall always says at a time like that: "Have ya paid your dues, Bruce?" "Yes sir, the check is in the mail."