The Black Hole (1979)

They should replace the ship with dollar signs.

1979 was a sneaky big year for science fiction on the big screen.

Mad Max was a low-budget dystopian revenge thriller that improbably launched a decades-spanning franchise. Alien was an expensive, space-based creature feature that also birthed (pun intended) a decades-spanning franchise of its own. Star Trek: The Motion Picture marked the first big-screen outing for the cult television series that, like its two contemporaries, still endures/exists today.

And then, in a quieter corner of the galaxy, Disney released The Black Hole — part gothic opera, part philosophical thriller, part toy commercial. It boasted a cast of recognizable faces, a budget twice that of Star Wars, and the participation of a prestigious composer. Best of all, it came from Walt Disney Productions, the long-time benefactor of children’s imaginations.

What could go wrong?

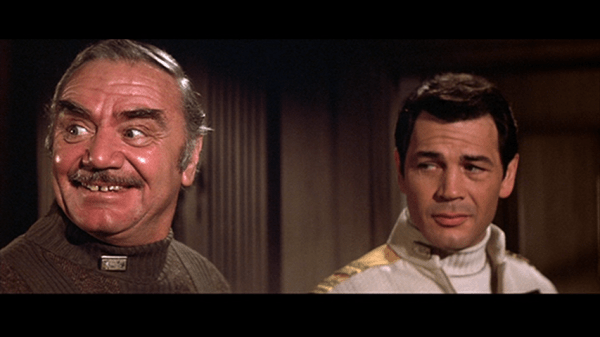

Seriously…look into my eyes…and TELL…me…

Quite a lot, apparently.

Children were frightened, parents were baffled, and the box office — though technically profitable — felt underwhelming compared to the film’s towering ambition. Critics of the time were almost united in exuberant hostility. Yet what they missed, perhaps because they simply weren’t ready for it, was that The Black Hole suggested something radical: that outer space could serve as the ultimate stage for psychological — even metaphysical — horror.

Ridley Scott’s Alien embraced the visceral side of that terror, while The Black Hole — almost accidentally — staked out a position in a genre that was perhaps not yet ready to be born.

Set in an indeterminate future, the research vessel U.S.S. Palomino is on its return voyage to Earth after a long deep-space mission. On board are the ruggedly handsome Captain Dan Holland (Robert Forster); planetary scientist Dr. Alex Durant (Anthony Perkins); first officer Lt. Charlie Pizer (Joseph Bottoms); Dr. Kate McCrae (Yvette Mimieux), the ship’s empathetic science officer; and Harry Booth (Ernest Borgnine), offbeat reporter for a great metropolitan newspaper.

Guess who’s who?

They detect a derelict vessel orbiting a nearby black hole and debate whether to investigate. The ship is revealed to be the U.S.S. Cygnus, a massive deep-space research vessel presumed lost for decades. Among the crew was Kate’s father, himself a respected scientist.

Now, there’s a moral imperative to land on board and look around.

The Cygnus lights up as they approach — as though it expects them. On board, they discover Dr. Hans Reinhardt (Maximilian Schell), the greatest planetary scientist of his generation, and the Captain of the ship. He reveals that the crew was evacuated during an emergency but did not survive.

Reinhardt’s only companions are now the army of robots he built to maintain the ship and Maximillian, an intimidating robot guardian armed with an array of weapons that seem somewhat over-the-top for a research vessel.

Research…to death!!

Reinhardt informs his visitors that Kate’s father has perished with the evacuees, but graciously offers them repairs and provisions to expedite their return home. Then he reveals his master plan: he intends to enter the black hole itself and discover what lies beyond.

Up to this point, The Black Hole presents as an operatic space procedural.

The crew of the Palomino speaks in dense technical jargon as they work, surrounded by detailed interiors and majestic exterior model shots. Legendary Bond composer John Barry provides a grandiose, almost ecclesiastical score.

Viewers at the time might have recognized a spiritual nod to the stately ceremony of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

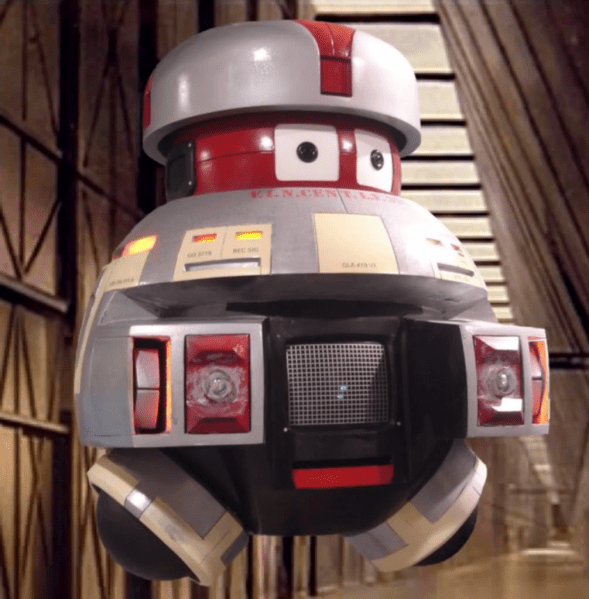

Meanwhile, the ship’s service robot, V.I.N.C.E.N.T. (voiced by Roddy McDowall), conducts an EVA repair on a tether. Oh — did I forget to mention him? The Black Hole was released in the long shadow of Star Wars; Disney clearly wanted to a taste of of Kubrick’s prestige and Lucas’s box-office lightning.

Years later, it seems to be going well...

The result is an aesthetic tug-of-war that’s jarring today and must have been bewildering in 1979. Parents expecting a lighthearted space romp found instead a film steeped in Gothic excess, isolation, and dread. The Cygnus drifts like a cathedral in space, lit from within, guarded by wordless drones, ruled by an autocratic zealot.

And yet…there are also wisecracking, googly-eyed robots, laser guns that make literal “pew-pew” sounds, and, while I’ve praised Barry’s excellent score, the movie’s brass happy secondary theme is the kind of thing Mel Brooks would savagely spoof years later in Spaceballs.

Still, at the core of The Black Hole (HA!) is a hauntingly simple horror story. What makes it work, at least for me, is that despite its tonal confusion and obvious commercial motives, The Black Hole never stops taking itself seriously.

V.I.N.C.E.N.T., and later his battered counterpart B.O.B. (Slim Pickens), were clearly designed to evoke the iconic machines of Star Wars. But where Lucas used his droids primarily as comic relief, Disney gives theirs genuine agency and emotional weight. McDowall’s voice performance turns V.I.N.C.E.N.T. into something oddly human — ironic, courageous, and intensely loyal.

Yeah, yeah…just trust me…it fucking works.

By contrast, the hulking Maximilian hovers silently in Reinhardt’s orbit like a mechanical avatar — the manifestation of the doctor’s intellect stripped of empathy. His menace feels almost supernatural.

But let’s not forget that there are humans at the core of this story.

If the Cygnus is a haunted house in space, Reinhardt is the mad scientist in the attic. Schell plays him with frightening conviction: a man so obsessed with unlocking cosmic secrets that he’s sacrificed his humanity to do it.

Durant, meanwhile, is so smitten with Reinhardt’s genius that he abandons his scientific objectivity. Perkins plays his awe as something close to worship, and his inability to confront his idol leads to one of the film’s most poignant moments.

I mean, he’s practically eye fucking the guy.

The Black Hole’s credibility rests not on its science but on its thematic sincerity.

The script and the presentation may be uneven, but a clear moral throughline survives the production’s well-documented chaos. Each character is distinctly drawn, and the writers’ intentions still shine through the noise. Every performer commits to that vision, giving moral weight to what might otherwise have been farce.

Forster’s stoic composure, Borgnine’s self-serving paranoia, even V.I.N.C.E.N.T.’s oddly mechanical nobility — together they suggest that none of these people are here by accident, but by design. Maybe the Cygnus didn’t find the black hole. And perhaps the Palomino didn’t “find” the Cygnus.

Perhaps each ship was summoned there.

The Black Hole suggests — ambitious stuff for a film designed to sell toys — that its characters are being tested: for curiosity, courage, faith, or hubris. The singularity itself becomes a kind of cosmic eye of judgment, silently watching — and finally weighing all of them.

The singularity effect itself, while scientifically absurd, more than serves its purpose both narratively and visually: an unforgettable marvel of 1970s practical effects — turbulent, furious, and awe-inspiring.

There he goes again…

This isn’t a film for scientists, and truthfully, it was never entirely suitable for children — at least, not in that sneaky-good year of 1979. The Black Hole shares very little with the romantic optimism of Star Wars. It plays more like a cosmic morality play, a modern myth about obsession and consequence. Its lack of realism isn’t a failure of imagination, but the very point of it.

In this universe, morality IS gravity, and we defy that at our own risk.

This is the least worst trailer I could find, as too many of the time, they pretty much show you the whole damn film. This is a legitimately good one, although it’s cut to resemble something more modern. But if you have any interest whatsoever in vintage cinema, I urge you to try and experience The Black Hole for what it is, what it tried to be, and what it almost accidentally achieved.

Categories

Bruce Hall View All

“When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favorite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol' Bruce Hall always says at a time like that: "Have ya paid your dues, Bruce?" "Yes sir, the check is in the mail."