The Surfer (2024)

Glorious.

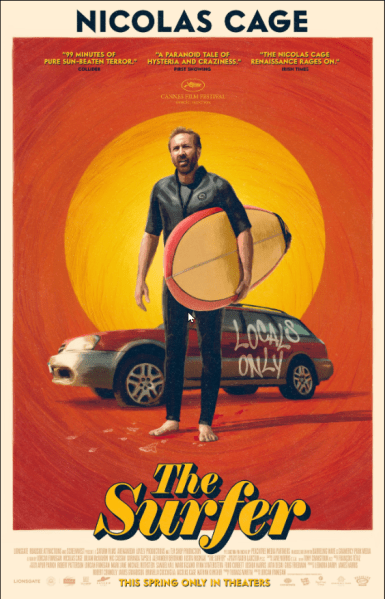

Imagine my surprise when I stumbled across The Surfer. The one-sheet has a dusky, retro vibe, featuring a grizzled Nicolas Cage carrying a surfboard against an amber sunset, flanked by a desecrated Subaru wagon.

I was stunned.

A low-budget, offbeat surf thriller starring the force of nature that is Nic Cage?

Why was I not informed?

In The Surfer, Cage stars as an unnamed man who returns to his Australian hometown with his teenage son, hoping to revisit the beach where he spent his youth. He wants to pass along the joy of surfing, a pastime that once defined him. To that end, the Surfer has poured his resources into trying to purchase the home where he grew up, in the fictional Australian town of Luna Bay.

It’s clear he’s hoping this experience will help reconnect him with his son and his estranged wife. But when we meet him, the Surfer is in a tough spot.

His real estate agent has informed him that he’s been outbid for the house and has a limited amount of time to come up with a counteroffer. His accountant insists it’s going to take time to put together the funds. And his ex-wife, while applauding his desire to reconnect with their son, has moved on to another relationship.

Even the Surfer’s own son (Finn Little) is skeptical to the point where, as I mentioned, he vanishes until late in the third act.

Father: “Hey, son, let’s go surfing!”

Son: “^^^”

Despite the odds being so heavily against him, the Surfer tries to seize the initiative, marching his son down to the beach to surf—likely knowing there would be trouble. Perhaps through a veil of righteous indignation or misplaced entitlement, he convinces himself it will work.

It doesn’t.

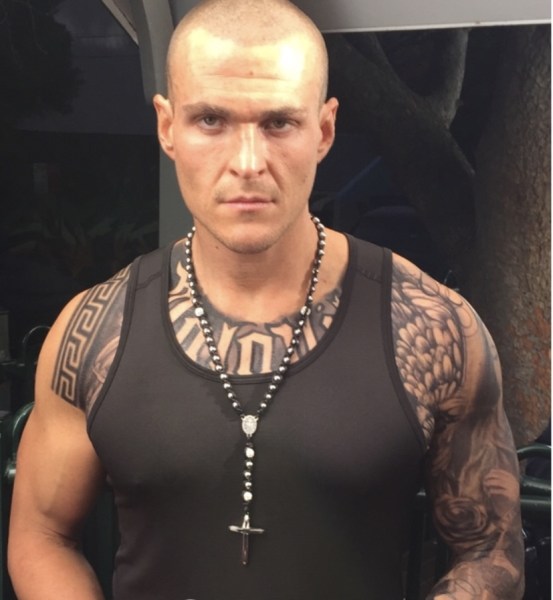

There’s already a group of locals at the beach, a gang of hard-drinking surf goons led by Scally (Julian McMahon), an enigmatic Svengali who seems to remember the Surfer from his childhood. But the “Bayboys,” as they call themselves, have a motto:

“Don’t live here, don’t surf here” — and they’re happy to use violence to enforce their credo.

Don’t take my word for it, take his.

This is the point at which the son disappears from the story and the Surfer begins a surreal, Twilight Zone-style journey through a seaside community where nearly everyone—from the Bayboys to the individual residents to the local police—is in the know on something the Surfer (and viewer) is excluded from. The conflict quickly escalates from juvenile acts of vandalism (i.e., the car on the poster) to wanton acts of physical brutality.

All of this is in the interest of driving “outsiders” from Luna Bay and is directly at odds with the Surfer’s almost pathological need to re-integrate his perceived family back into the community.

He’s a quietly desperate man chasing a romanticized perception of something that never truly existed.

The pull of The Surfer to me ultimately became this central rivalry, superseding any sense of narrative logic. The Surfer is not a logical film, and I’m not sure it meets the criteria for truly being a philosophical one. Still, I felt drawn to the conflict, mainly because of the film’s success in creating the weird little world in which it occurs.

I am not familiar with Australian director Lorcan Finnegan, and I can’t say that I wasn’t expecting this to be something wilder than it is, given Cage’s (valid) reputation for occasional overreach.

Don’t take my word for it, take his.

However, I also can’t say that I was entirely satisfied with The Surfer at the end; this is an unconventional film that commits entirely to the concept.

At multiple points, there are critical conversations between Scally and the Surfer, where they have their moments, exchanging points of view and challenging each other’s position. It is in these moments that the material shines, giving a sometimes uneven and confusing narrative a charge of primal energy. They are two men with competing visions of the same patch of land, and only one can win.

There’s also a wildcard involved: a seemingly deranged homeless man who lives in the Subaru shown on the one-sheet. He serves as something of a theoretical bridge between what is real and what is less-than-real about this story, and I won’t deny finding myself bewildered by it at times.

Nonetheless, the middle section of The Surfer leads us through a visual, visceral deconstruction of a man as he transitions from one society to another. I might even go so far as to call it an “immigration story,” but not in the politically charged way the word “immigrant” is perceived by some these days. I mean it in the sense that when this film began, I listened to Nicolas Cage—a man who has no hope in hell of pulling off an Australian accent—convince me, and the Bayboys, that he had grown up in Luna Bay but been forced to migrate to California.

Borb in the Bay, raised in the Valley, baby.

And now, after (in his mind) losing his identity somewhere along the way, he was eager to reconnect with his roots. I connected with this part of the story—not because I share a similar yearning but because it was effective. The Surfer is far less about surfing than about suffering, belonging, yearning, and transference.

Don’t take that to mean I see this as high art. The old man, the wild visuals, and some of the baffling choices Cage’s character makes lent the film an allegorical gloss that left me conflicted.

When it was over, I found myself feeling two things at once:

On one hand, I sympathized with Cage’s forlorn Surfer, flaws and all—his clumsy determination to reconnect, his stubborn insistence on trying to shape the world around him. On the other hand, I couldn’t shake the sense that the story had sidestepped a more meaningful resolution than the one it chose. That tension left me both satisfied and annoyed.

I was impressed by the film’s ambition but was left faintly frustrated—not by where it landed, but by how. The best way I can put it is to imagine finally obtaining something you’ve struggled long hours for, only to find the final step carried out by someone else.

Something like that.

Maybe this is more of an emotional and visual tableau than it is a motion picture, and while that might be confounding for some, I found it to be oddly invigorating. Cage’s performance is unexpectedly restrained, and his scene chemistry with McMahon often helps the film make up ground after a few visually charged sections that some might find laborious.

The Surfer won’t strike everyone the way it struck me; this isn’t a film that hands you a conclusion. Instead, like the waves beneath your board, it asks you to feel your way through.

Categories

Bruce Hall View All

“When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favorite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol' Bruce Hall always says at a time like that: "Have ya paid your dues, Bruce?" "Yes sir, the check is in the mail."