Alien: Earth, Episodes 1 and 2 (2025)

The Alien franchise has spent decades chasing its own tail.

Sometimes it has leaned into horror, sometimes into action, and occasionally into philosophy — with wildly mixed results. What it hasn’t done, until now, is (credibly) broaden its net to ask what its dark universe actually means for humanity.

That’s the surprise of Alien: Earth, a series that manages to honor the atmosphere of Ridley Scott’s original film without worshiping it, while expanding the franchise in both unsettling and invigorating ways.

The first two episodes waste no time setting the tone, after easing us back in with familiar rhythms.

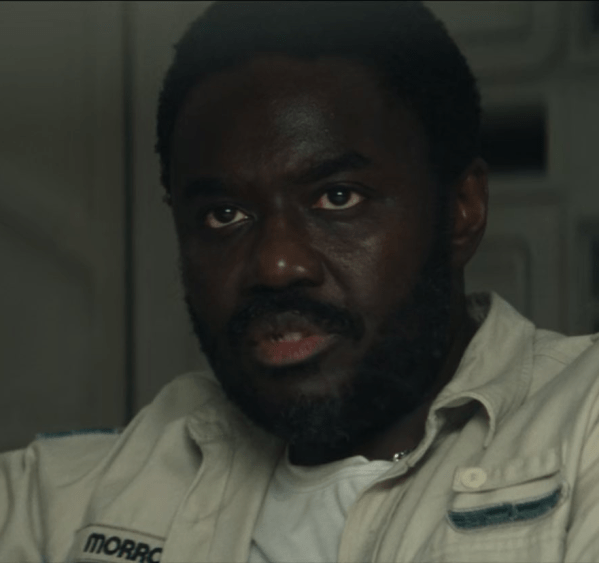

We open on a few beauty shots of the USCSS Maginot drifting in space before cutting to its crew climbing out of stasis pods in their underwear and bickering over breakfast. Their conversation follows a rhythm any Alien fan will recognize: working-class banter, personalities revealed through casual ribbing, the sense that these are regular people who just happen to be in space. The visual echoes to the Nostromo crew are unmistakable. For example Morrow (Babou Ceesay), the Maginot’s resident “cyborg” (more on that later), is a coldly suspicious model of efficiency.

Just putting it out there.

It’s all familiar, all comforting — right up until the show turns everything on its head.

The Maginot, it turns out, is carrying a secret payload coveted by the Weyland-Yutani corporation: not just the xenomorph we all recognize, but a menagerie of other horrors from the same ecosystem. The implication is chilling — that the xenomorph isn’t a corporate creation at all, but the natural product of a world where everything is a predator and survival itself is an arms race.

Interestingly, this echoes the original Alien, where the same (evil) corporation schemed to smuggle a lone creature back to Earth at the expense of an unsuspecting crew. But Alien: Earth is set two years earlier, and this timing immediately raises a host of questions the series will have to reckon with before it ends.

Weyland-Yutani: A history of being shitty.

Whatever hellscape the Maginot’s cargo evolved on, it isn’t entirely different from the cultural atmosphere of Earth itself. By 2120, world governments have ceded power to corporations, and two giants dominate: Weyland-Yutani and its closest rival, Prodigy Corporation (no relation to the weaksauce 90’s Internet provider). Each has staked its future on synthetic life, though in very different ways.

An opening card informs us that Cyborgs are humans rebuilt with mechanical parts. Synths are the artificial companions we already know from the franchise: fully constructed beings with sentience engineered into them. But Prodigy pushes things further with Hybrids — synthetic bodies carrying the digitized minds of terminally ill children.

Let that sink in.

The company’s young CEO frames this as an act of both innovation and mercy, but the reality is far less benevolent. Only children’s minds are “flexible” enough to survive the transfer, which makes their exploitation not just possible, but essential to the technology.

So on one side of the problem, you have a ship filled with bloodthirsty predators, the apex hunters of an alien ecosystem. On the other, a planet dominated by soulless corporations that have effectively learned how to take the “human” out of humanity. And when something (still unknown by the end of episode two) goes catastrophically wrong aboard the Maginot, sending it plunging toward Earth in the opening minutes of the pilot, the series plants a flag right in the center of it all:

What does being human even mean anymore — and how should we value it?

Unlike most of Alien canon, this isn’t just another story about a monster loose in the dark. It’s about a human race facing monsters after already having become monstrous itself — through the things it builds, and the gambles it takes.

The crew of the Nostromo never had a chance.

Fucked…all of them…fucked.

The Maginot crashes on Prodigy Island, the isolated enclave that serves as both corporate headquarters and bustling metropolis for Prodigy employees. This doesn’t sit well with the formidable Ms. Yutani (Sandra Yi Sencindiver), who quickly dispatches a strike team to retrieve her “property.” It sits even less well with Boy Kavalier (Samuel Blenkin), the barefoot trillionaire and “boy genius” behind Prodigy. Impulsive, hubristic, and very high on his own supply, Kavalier presides over the company that pioneered Hybrid technology.

He has taken a personal interest in the six prototypes he’s created so far — so much so that he’s indoctrinated them into the mythos of Peter Pan, going so far as to name his first Hybrid “Wendy” (Sydney Chandler).

True to her namesake, Wendy reads as imaginative, responsible, and faintly matronly, not because she chooses to be, but because, like her compatriots, her childhood has been irretrievably stolen. When the Maginot crashes into the heart of Prodigy HQ, Wendy and her “Lost Boys” — Slightly (Adarsh Gourav), Curly (Erana James), Nibs (Lily Newmark), Smee (Jonathan Ajayi), and Tootles (Kit Young) — are sent on what is framed as a routine search and rescue.

On one hand, this looks like an opportunity. Hybrid bodies are far stronger, faster, and more resilient than any human; they could be useful in hazardous environments. And yet, they could also become extraordinarily dangerous if they chose to rebel. Set that against the fact that these bodies house the minds of literal children, already traumatized by terminal illness, and the whole concept begins to look like the worst idea in the history of ideas.

For this reason, the team is led by Kirsh (Timothy Olyphant), the dispassionately avuncular synth responsible for training Wendy and the others. His frosty demeanor hides an intense curiosity and a quiet, machine-like resolve, and Olyphant plays him with a contained physicality that suggests both he and Kavalier know much more than we have been shown.

Tell me I’m wrong.

When the inevitable happens and the Hybrids encounter the alien freakshow aboard the Maginot, I kept thinking about a child’s mind trapped inside a combat android, unable to develop or mature like a normal person. What kind of being would that produce after a few years of living this way?

Would it think or act any differently than the creatures it was sent to fight?

Despite the ghastly ramifications of this, the world these characters inhabit is no post-apocalyptic hell. Prodigy City isn’t a dystopia; its residents live within visible strata of prosperity — some comfortable, others less so — but there are no trashcan fires, and no rain-slicked neon streets. It’s a functioning capitalist metropolis, prosperous if inequitable, but not far removed from our own world. The difference is that life-and-death decisions for the entire planet rest in the hands of a few corporate rivals, like petty stepsiblings playing god.

The human toll of their ambitions never enters the equation. For Yutani and Kavalier alike, if their aspirations happen to cost the lives of everyone else on Earth, they would simply continue the competition without us.

It doesn’t take a genius to see the real-world parallels.

Please enjoy this random image I found on the Internet.

All of this would feel heavy-handed if the show weren’t also a pleasure to experience. The production design strikes a remarkable balance, reviving the retro-futurism of 1979 — clunky keyboards, glowing CRT displays — while layering in tactile touches and even the occasional bursts of extended daylight. Likewise, despite the grimness of their situation, we’re still allowed to see bits of whimsy emerge from the children as they navigate the world, adding elements of humor and warmth to the franchise missing since the James Cameron days.

The score, by Jeff Russo (Fargo, Legion, Star Trek: Discovery), follows suit: minimal, eerie, and alive with interesting textures. It’s creatively compelling and effective in the way it weaves in music cues from the original film.

It’s all in service of a world that feels lived-in and consistent, but not frozen in nostalgia. Alien: Earth knows where its roots lie, but it also confidently signals its intent to move forward.

This time, the aliens come holding up a mirror, widening the stage to show that there are all kinds of ways to respond to competition — evolutionary and otherwise. The series shifts the focus away from the xenomorph alone and toward the larger question of what kind of organism humanity itself is becoming.

And in doing so, it delivers two of the most compelling hours this franchise has seen since 1979.

For the first time, I’m not watching Alien for the creatures in the shadows.

I’m watching for what it reveals about us.

Alien Earth can be found on FX/Hulu

Categories

Bruce Hall View All

“When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favorite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol' Bruce Hall always says at a time like that: "Have ya paid your dues, Bruce?" "Yes sir, the check is in the mail."