Back to the Future (1985)

The Cybertruck of its day.

Each time you watch a movie, you see something new.

At first, it’s just about following the story. A few times later, you’re able to recite your favorite lines. By the tenth viewing, you can probably quote it from start to finish. And from that point on, it becomes exponential. People start dressing up like the characters, quoting them in real life, and spending valuable time using the word “canon” on the internet.

You stop watching the movie and start living it. And a hundred times after that, you start believing you understand the DNA of the thing.

And that’s where I am with Back to the Future.

Have you ever read the script to a movie you love – just the script, to see how it feels – and tried to imagine what it might look like before any of the onscreen magic? Think Richard Donner’s Superman without the score and the most perfect lead ever. Or how about The Bourne Identity with no camera movement, just storyboards. And how about The Usual Suspects without that eclectic cast – just words on the page?

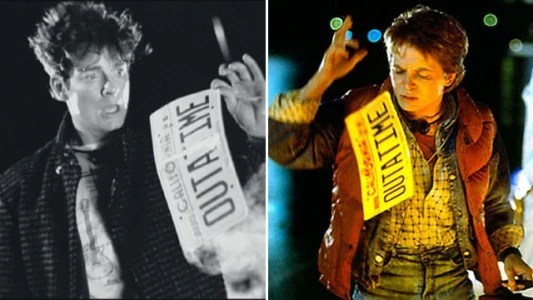

Now imagine being Eric Stoltz, the original Marty McFly. Imagine reading Back to the Future in that vacuum – before the DeLorean, before the delightful color palette, before Huey Lewis bewitched both middle-class children and their mothers. Stoltz saw a different movie entirely, and I get it. On paper, it’s a matter of perspective whether or not this is a comedy. If anything, it’s an existential nightmare with Oedipal overtones generated by a protagonist whose obliviousness nearly consigns him to literal oblivion.

Ever feel like you just don’t…belong?

While I can’t say, even after possibly a hundred viewings, that Back to the Future is a flawless story, it IS a flawlessly executed one. It’s the best possible version of a narrative that could have gone a dozen other ways – most of them darker, weirder, and ultimately far less beloved.

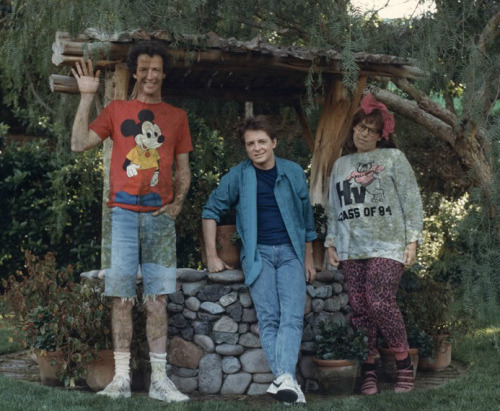

You know the deal: Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox) is a neurotic teenager whose sharply fractured home life can be traced directly to his family’s deep historical entanglement with their equally malfunctioning community. His only friend is a wild-haired inventor, Doc Brown (Christopher Lloyd), who’s built a time machine out of a DeLorean – and instead of unveiling it before the world’s scientific community, he decides to flex with it in front of a teenager.

The length of the antenna is…unprecedented, Marty.

Things go predictably sideways. Doc is seemingly killed. Marty gets flung into the past, interferes with his parents’ first meeting, and ends up entangled in a slapstick love triangle with them. With help from the younger Doc and an unwitting assist from local bully / violent sociopath Biff Tannen (Thomas F. Wilson), he manages to save his parents’ relationship before it even starts – but not before suffering a concussion, inventing the skateboard, making out with his mom, and casually appropriating an entire musical genre.

When he returns to 1985, Marty finds his life transformed – his modest, lived-in family home is now a Capitalist fever dream of affluence and excess. His father, George (Crispin Glover), is a successful author. Lorraine (Lea Thompson) glows with happiness. Biff is neutered into a car-waxing doormat. The implication is that no amount of emotional growth or family bonding can beat a ton of money and a shiny truck.

Ok, I kind of wanted one too.

And let’s not forget – we never find out why Doc built the time machine. The DeLorean is almost incidental to the larger plot. Doc’s recklessness kicks the story off. Marty’s impulsiveness nearly erases himself from existence. George is a voyeuristic shut-in, Lorraine drinks and smokes and chases boys, and Biff is a cruel and unrepentant creep.

These are deeply irresponsible people who each just might deserve comeuppance a little more than they deserve redemption.

And yet we love them and forgive them.

Why? Because Back to the Future is an exercise in tone more than logic or ethics, and it executes its will with meticulous grace. The sharp cinematography, bright colors, and fizzy performances all tell us the same thing: no matter what you’re seeing onscreen, don’t worry – it’s all going to be okay. The film triumphantly ends with the best line of the story – the literal promise of a sequel – followed by Huey Lewis and the News, off the top turnbuckle.

Kids across America – and their moms – were never the same again.

There was no way to not love this movie.

But go back to my guy Stoltz again, holding that script in 1985 with no special effects, no score, and no half-century of hindsight. What you’d see might not necessarily be a comedy – it might clock as an extended and particularly bleak episode of The Twilight Zone (kids: Black Mirror). What if this wasn’t Marty’s personal, financially-very-lucrative Hero Journey?

I accept my fate! / No way, I want that truck!

What if this is actually the story of a troubled kid, one who senses something is deeply off in his world but can’t quite name it? A story where his best friend is a narcissistic man-child with dominion over the universe, time itself is unwinding around him, and the one variable that doesn’t belong strikes a bit too close to home?

And maybe George McFly has known all along. Perhaps the novel he’s working on is a thinly disguised chronicle of the events of the film. He’s been waiting for Marty. And when the time comes, they make a pact. George reveals that Space and Time themselves are broken, but not because of history.

It’s because of Marty. And the only way to stabilize the timeline is for Marty to be removed from it. So Marty spends a little too much time with Lorraine in the front seat of that 1949 Packard, and in a moment of existential horror, is erased from the story.

This is what happens when you make out with your Mom, Marty! You get an inconspicuous blob, and an eight foot tall circus freak whose beltline comes up to your nipples…(belch)!

And yet the timeline doesn’t collapse – it improves. Marty’s family thrives. Biff is diminished. The community grows. Doc alone fares poorly, becoming a tragic wanderer, haunted by guilt and traveling forever in search of the one reality where Marty might return without everything else unraveling. That’s the Donnie Darko version. The Blade Runner version. Maybe even the fucking Oldboy version.

Ok, sorry. I got too dark.

Hey, come on. Stop crying. Marty might also return home just as he does in the original, expecting everything to have changed, only to find that nothing has. The message would be that the past is not something which can be fixed – we are the sum of our choices and decisions and must live with them, always. And if we want our lives to improve, that work has to come from within.

The problem was never the timeline – the problem was always Marty. Happy now? I hope so, because Stoltz wasn’t wrong. He was just a strong actor, cast in the wrong picture.

I imagine the greatest gift of Back to the Future is that it contains, within it, every possible version of itself. But what is ultimately delivered to the audience is a perfect shell wrapped around those many darker possibilities. It perfectly presents as a story of familial bonding, community spirit, and personal redemption, while also quietly suggesting that time, identity, and consequence are far more fragile than we’d like to believe.

Both Zmeckis and Stoltz got it.

And maybe…that’s why we’re still talking about Back to the Future forty years into the future.

Categories

Bruce Hall View All

“When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favorite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol' Bruce Hall always says at a time like that: "Have ya paid your dues, Bruce?" "Yes sir, the check is in the mail."