The Magnificent Seven (1960)

Warning: This movie could get you pregnant.

Today’s cinematic landscape is littered with superhero stories, both good and bad. The financial linchpin of the film business has been, for some time, spectacle-driven franchises, largely written around similar templates and largely containing similar characters. Chances are, the climax of the movie will involve six or seven indestructible people punching each other in the middle of an urban intersection as terrified citizens flee the broken water mains and toppling buildings.

So many of these films are made – and persistently remade – that they become difficult to tell apart and increasingly difficult to anticipate with anything approaching excitement. But they’re going to keep coming because Hollywood has always required tentpole films – guaranteed moneymakers that appeal to a mass audience.

For at least a generation, this has meant superhero pictures. The nineties ended with a string of Tarantino clones but began as an extension of the 1980s, when audiences couldn’t get enough of oiled-up musclemen mowing through crowds of faceless henchmen with a machine gun.

I call this the One Man Army age.

The 1970s were the Age of the Director. Long, deliberately paced, prestigious monuments like The Godfather, Barry Lyndon, and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest were the darlings of the day. Chinatown? The Shining? The Exorcist? Sorcerer? Directors were allowed to do whatever they wanted, and some very strong, very long movies were the result.

Asses across the country went numb. But before that?

Westerns.

Westerns were not just a genre; they were the genre. For decades, they dominated the American entertainment landscape in ways far more pervasive than superheroes. It’s hard to overstate the ubiquity of Westerns in mid-20th-century America. They were TV shows, matinee staples, prestige pictures, pulp B-features – you couldn’t throw a saddle on your horse without hitting one. The romanticization of 19th-century American expansionism was an omnipresent aspect of the age, permeating every facet of society like institutionalized guilt.

Who can say why?

Westerns were the lens through which great actors and directors questioned humanity at that time. The 1950s provided one high point after another in this regard. 1956 brought us The Searchers, perhaps John Wayne’s most critically acclaimed role. The next year was 3:10 to Yuma, A tight, suspenseful morality play starring Glenn Ford and Van Heflin. Then there was Wayne again in Rio Bravo (1959), your grandfather’s all-time favorite. Each film examined the human condition against the unforgiving backdrop of frontier life.

And then, something extraordinary happened. In 1954, legendary Japanese director Akira Kurosawa made Seven Samurai, widely considered one of the greatest films of the 20th Century and the bellwether of ensemble action films. Set against the backdrop of ancient Feudal Japan – that country’s version of our Wild West Mythology – Seven Samurai was an unforgettable character study of heroism through sacrifice. It was a story that sang globally and resonated deeply with the American film community.

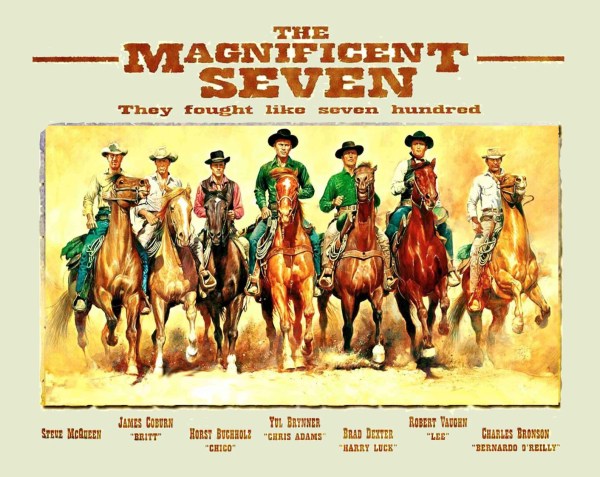

It also gave us this kickass still, so you’re welcome, People of Earth.

In 1960, an American remake was released, set in a small village on the Mexican-American border. The inhabitants live under the thumb of a marauding bandit named Calvera (the immortal Eli Wallach), who returns every year to steal the villagers’ harvest. Desperate for help, the locals pool their resources and travel across the border into the United States to buy weapons. Instead, they’re persuaded by a drifter named Chris Adams (Yul Brynner) that they’d be better off hiring gunmen to defend the town.

Chris is a laconic and principled gunslinger who wears all black, has a mysterious accent, and does not suffer fools. He helps recruit six other fighters, each with his own set of motivations:

- Vin Tanner (Steve McQueen) is a smooth-talking drifter with sharp reflexes and cool confidence. McQueen is an undisputed legend, but he was not Yul Brynner.

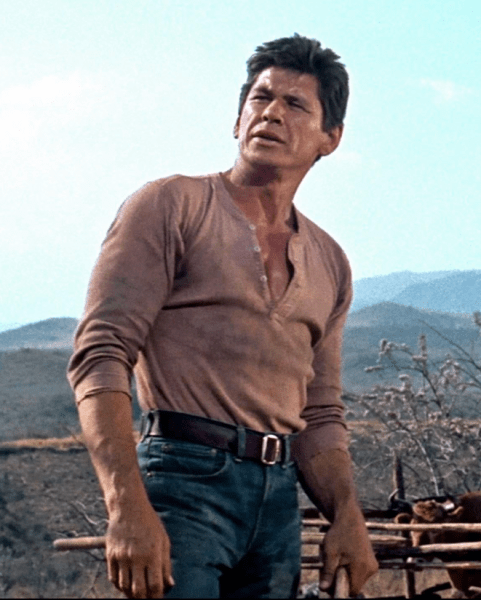

- Bernardo O’Reilly (Charles Bronson), a mixed heritage laborer-turned-gunman, is deeply down on his luck. Bronson would go on to fame as his own genre of cinema tough guy.

- Lee (Robert Vaughn), a once-feared sharpshooter haunted by frayed nerves and past trauma. Vaughn would achieve later fame in The Man From U.N.C.L.E.

- Harry Luck (Brad Dexter), a loudmouth opportunist, is convinced there’s gold to be found. Dexter was an underrated talent, perhaps the Michael Madsen of his time.

- Britt (James Coburn) is a strong, silent knife thrower with a Zen-like calm and fast hands.

- Chico (Horst Buchholz) is a fiery, impulsive young man trying to prove himself. He performed all his lines phonetically and did not actually speak English. For my money, this is the most incredible performance in the film.

The Seven ride south and arrive at the village, where they begin fortifying the town and training the locals to fight. At first, the villagers are frightened of the Seven, but they gradually form bonds. Bernardo and Chico, in particular, begin to form strong ties that, in time, might bind them to the town permanently.

The payoff of The Magnificent Seven lies in watching these violent, independent predators learn what separates them from actual killers. And it’s not even the ability to form bonds – even criminals care about each other. It’s about finding a reason to put down roots and to care about something larger than yourself.

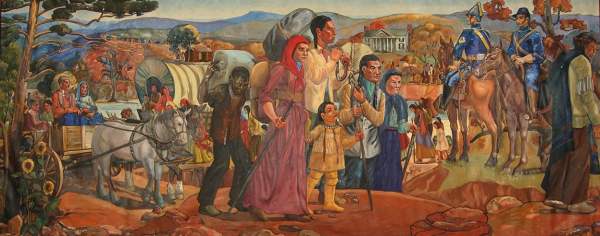

Like, this much larger.

I’ll just say this now: Seven Samurai is a flawless masterpiece. It redefined cinematic structure, rhythm, and depth. It is taught in every serious film school. It is, overall, a superior film to The Magnificent Seven. But what The Magnificent Seven does, and what makes it endure with nearly equal mythic power, is not mimicry but translation. This is one of the rare, near-perfect genre remakes, a film that takes the thematic soul of its source and breathes it into a different cultural myth without losing the weight or wonder of the original.

If Seven Samurai is a philosophical elegy, The Magnificent Seven is an American hymn (look no further than the iconic theme song, written by the great Elmer Bernstein). Kurosawa’s film lingers on suffering, class division, and the inevitable obsolescence of warriors—all valid and compelling themes within Japanese life at the time. But American director John Sturges gives us something cleaner and more identifiable for Westerners – a simple ode to raw courage, coated with dust and clad in leather. Both films work brilliantly but for entirely different reasons.

My favorite character from The Magnificent Seven is easily O’Reilly, played by Charles Bronson. In my mind, he’s the heart of the film. This gigantic, heavily muscled brute quickly becomes a role model for the children of the town, making sure to comport himself with dignity and honor in their presence, and – for a man who laments never having had a family – proves his fatherhood chops when it matters most.

The final act of The Magnificent Seven ties together the stories of all seven gunfighters, with perhaps the most poignant being those of the survivors. Each of the Seven is in need of some form of redemption, and ironically, they all come to learn that getting the result you want is not necessarily better than getting the result you need and that survival itself does not necessarily equal redemption.

It’s hard out there, on the prairie.

Categories

Bruce Hall View All

“When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favorite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol' Bruce Hall always says at a time like that: "Have ya paid your dues, Bruce?" "Yes sir, the check is in the mail."