The Game (1997)

Oh, the possibilities…

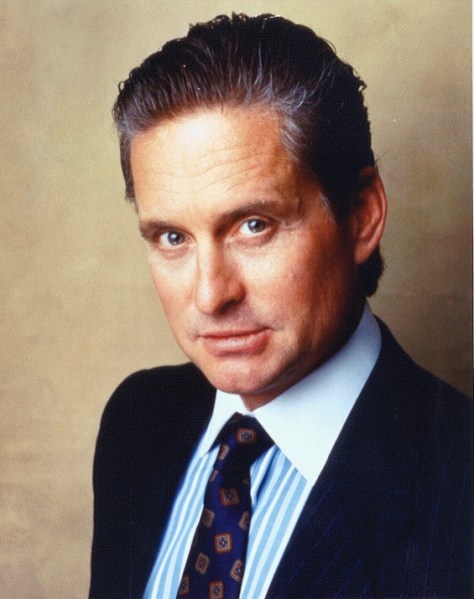

In another place and time, people went to the cinema. Depending on the MPAA rating, they gathered their family, their significant other, or a rumpled raincoat and sunglasses and shuffled off to a theater for entertainment. Today, everything is IP-driven, but back then, it was often the lead actor’s name on the marquee that drew you in. Michael Douglas is the son of an icon – the legendary Kirk Douglas – and you can sense his father’s essence in every step, every word, and every gesture.

BAM – You’re pregnant.

But Michael forged his own identity, taking the mantle of his father’s hyper-masculinity and distilling it into something more restrained and refined, suited to the dramatic highs and lows of the late twentieth century. That alone is reason enough to revisit him in David Fincher’s The Game. Coming from the enigmatic auteur behind Se7en and the maverick visionary who would later confuse a generation of incels with Fight Club, with The Game fincher delivers a procedurally effective but emotionally callous entry in the psychological thriller genre.

Nicholas Van Orton, played by Douglas, in full Corporate Ghost Mode, is a man whose emotional detachment has fossilized into a worldview. As the film opens, Nick is drifting through what should be another ordinary day as a high-powered investment banker. He is wealthy and handsome, drives a BMW with a built-in car phone, lives in the biggest house on the block, and commands fear and respect in every room he enters. But this day is different—it’s his 48th birthday.

BAM – twins.

Many years ago, Nick’s father committed suicide on his 48th birthday by leaping from the roof of the family estate, locking eyes with young Nicholas as he jumped. Nick grew up dedicating his life to restoring his family name, protecting its wealth, and mastering its reputation. He does not suffer fools, has no patience for jokes, and even less for losing money.

Yet beneath the icy demeanor is a discreetly generous soul—his employees absorb his irascibility with grace because they genuinely seem to respect him. And yet, he shuns the birthday wishes of his business staff, his personal assistants, and even his oddly empathetic ex-wife. On the surface, Nick has it all—but on this day, he broods over his father’s memory and struggles to decide whether this date should mean more than he wants it to.

Then his younger brother Conrad (Sean Penn) arrives. Estranged and volatile, Conrad lives the life of an entitled drifter, squandering his inheritance on every indulgence imaginable. He offers Nick a mysterious birthday gift from Consumer Recreation Services. Nick accepts—reluctantly at first, then with growing investment—as strange things happen almost immediately. When he accepts the Gift, Nick finds his world slowly unraveling. An attempt to fire an underperforming colleague becomes a farce. A childhood clown figure appears in his driveway, holding a mysterious key.

BAM – Clowns

Surveillance follows him across cities. Someone has infiltrated his life.

It begins subtly: a jammed briefcase lock, an exploding pen—a few eerie coincidences. But then it escalates. A missed dinner with Conrad leads Nick to Christine (Deborah Kara Unger), a tough, guarded waitress. Ten minutes after that, they’re in an ambulance with a dying man and a suspicious cop.

The pranks have turned perilous. And as the attacks grow more pointed, they begin to affect the professionalism at the core of Nick’s identity. And if this weren’t enough, the level of penetration eventually envelops his personal privacy and internal sanity. With The Game, Fincher crafts a glossy web of paranoia that threatens to devour his protagonist entirely.

The deeper Nick digs, the less he knows: Is CRS real? Is Conrad lying? Is Christine innocent or part of the scheme?

The Game sits between Se7en and Fight Club in Fincher’s filmography. That placement may explain why it’s often overlooked, bookended by a breakout hit and a cult classic. But while Se7en drags us through moral hell and Fight Club revels in stylish anarchy, The Game is quieter: a tightly wound character study disguised as a psychological thriller. Think North by Northwest by way of the mid-’90s. It’s old enough now to feel charmingly dated—tube monitors, airport confrontations, and mobile phones that exist only when the plot demands it.

BAM – doesn’t work underwater.

However, its inherently cool and meticulous style gives The Game unexpected staying power. Where Se7en is grimy and Fight Club chaotic, The Game is sterile, elegant, and eerily calm. As always, Fincher’s filmmaking is controlled down to the micron. Douglas plays Van Orton as an older echo of Gordon Gekko—a man of power forced to turn inward. Sean Penn runs the emotional gamut with restraint, while Deborah Kara Unger’s cool, unreadable performance keeps us guessing.

The plot, however, throws so many twists so quickly that by the third act, it starts to rattle under the force of its own machinery. Credit is due to writers John Brancato and Michael Ferris for crafting a compelling high-concept premise, but it’s Fincher’s vision and formal discipline that elevate the material. By the end, we’re left to wonder: Was this an elaborately stylish thriller or an incurious farce? The story hints at the potential of personal transformation but delivers something much more ambiguous and frustrating. The emotional stakes are brushed aside for an easy, ironic shrug.

Two hours of stylized intrigue land softly on the doorstep of fable.

Ugh! But it’s also so goddamn cool!

BAM – Guns!

Yet still, The Game seems afraid to follow through on its heaviest questions: Can trauma be outsourced? Can emotional walls protect or only imprison? Is total control of one’s environment the acceptable opposite of personal connection? Isn’t it fun when a movie zigs instead of zags? Most of the time, yes. But here, the final moments are all zag.

Fincher’s control and Douglas’s presence keep The Game from slipping through the cracks. The film has its issues—the third act strains under its own complexity, and the resolution doesn’t fully deliver on the emotional stakes—but it’s executed with such confidence that it remains compelling, almost to the end. Douglas grounds the picture, even when the plot threatens to spin out of control.

The Game may not be Fincher’s best work, but it’s a strange, stylish flash in the pan that’s well worth revisiting. It elevates a less-than-ideal story with a lottery pairing of actor and director.

Categories

Bruce Hall View All

“When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favorite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol' Bruce Hall always says at a time like that: "Have ya paid your dues, Bruce?" "Yes sir, the check is in the mail."