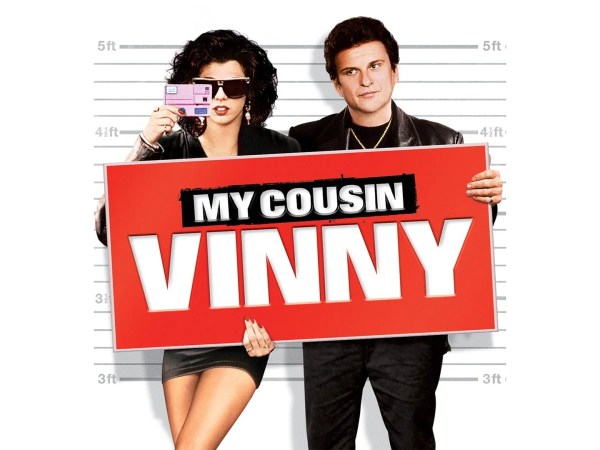

My Cousin Vinny (1992)

Over a series of establishing shots—two college kids on a cross-country drive, a small-town roadside with hubcaps and dirt for sale, a slow drift into unfamiliar territory—My Cousin Vinny tells you exactly what kind of film it intends to be—light on its feet, sharp in its details, and entirely unbothered by the idea that it might not fit neatly into a tonal box. The imagery is dissonant, but the music hums with confidence.

It’s just off-kilter enough to hint at dread, while still quietly reassuring you:

We’re gonna have a good time.

It’s a tonal promise, and it’s one the film never breaks. Even as the premise darkens—and it does—the overall energy remains buoyant. Billy (Ralph Macchio) and Stan (Mitchell Whitfield), a pair of likeable New Yorkers, wind up in serious trouble when they roll into a small Alabama town on their way to California to attend college. Their arrival coincides with a heinous crime, and in a case of mistaken identity taken straight from an episode of Brooklyn Nine-Nine, our boys are on the hook for murder.

Luckily, despite coming across like characters from a 1960’s stage musical, Billy and Stan have an ace up their sleeve. Billy discovers that his cousin Vinny, based back in Brooklyn, happens to be an attorney. But of course, when we first meet him, we discover that Vinny (Joe Pesci) and his partner Mona Lisa Vito (Marissa Tomei) aren’t quite what we expect. They’re flashy, defiantly informal, and dressed with the energy of pool hall regulars who never got the memo that court is a no-leather-jacket zone.

I mean, really…

This setup could have easily been presented as a ludicrous spoof, but My Cousin Vinny successfully walks a tonal tightrope that few comedies can match. It’s broad without being dumb, clever without being smug, and funny without ever undermining what is a fundamentally very serious story. There are murder charges, jail cells, and courtroom proceedings—but Vinny respects the stakes while maintaining amity with the audience. We don’t want this to become a story about actual guilt or moral ambiguity—we want to see the right people win, and the film honors this without compromising its integrity.

With the same cast and a different soundtrack, you can easily imagine this as a slick, hard-R legal thriller, directed by someone like Jonathan Demme or Sidney Lumet. Our leads are all capable of delivering a dramatic range and can convey intensity when required. But this film doesn’t need them to be grim or hardened. It asks them to be sharp, vulnerable, and funny—and they are. They rise to meet the vibe the film requires, rather than bending the film to suit some other register.

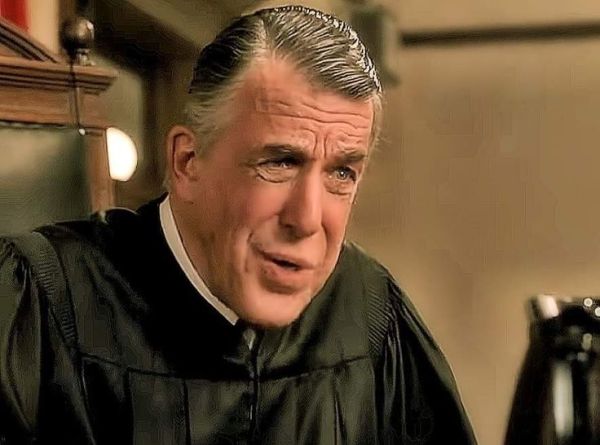

Even the supporting cast—many of them seasoned character actors with serious dramatic chops—play their roles with the same grounded sincerity. Fred Gwynne, Lane Smith, Bruce McGill – this is a movie full of people who know how to hit the funny without ever making fun of the story.

That balance is no accident. Director Jonathan Lynn has an evident talent for managing tonality, which I would stop just short of calling his trademark. But for the sake of argument, in Clue, he leans into slapstick while maintaining a thread of distinct tension. In My Cousin Vinny, he applies that same control to a more grounded story with higher stakes, and the result is easily the best film of his career.

However, the heart of the film lies in the dynamic between its leads. What might initially read as broad stereotypes—a loudmouth New York lawyer and his even louder fiancée—quickly reveals itself as something more innovative and warmer. These two don’t just trade punchlines; they have a much more complex dynamic. They challenge each other, support each other, and disagree in a way that’s oddly productive and entertaining. There’s a hotel room scene, played lightly, where you realize they’re not arguing so much as communicating. They bicker their way toward clarity. They’re not stumbling into compatibility; they’re discovering that they’re already a high-functioning team.

One of the film’s most intelligent choices is to treat its characters as inherently competent, even if they don’t yet know how to apply their talents. Vinny doesn’t become a “real lawyer” by learning to imitate the professionals around him. He improves himself by learning how to channel what he already does well—asking questions, spotting contradictions, listening for what doesn’t make sense—into something structured and strategic. Tomei’s character, meanwhile, doesn’t become important because of a single pivotal moment. She’s essential all the way through, gradually emerging as the one who gives shape and order to Vinny’s instinct.

Mona Lisa does not fuck around.

She doesn’t just believe in him—she makes him possible. Defending the boys is a team effort, and it works because each person brings something essential.

If the film stumbles at all, it’s during the brief appearance of a public defender played so broadly he feels like he’s stepped out of an entirely different, more cartoonish movie. His energetic level of ineptitude feels out of step with the rest of the film’s tone—one of the few moments where the story does seem to condescend to itself.

Technically, the rest of the movie is as precise as its storytelling. The sound design is clean, layered, and expressive, from courtroom ambiance to the hilariously escalating cacophony of the motel scenes. Thunder and lightning serve as dramatic punctuation without tipping into melodrama. Even the soundtrack, dated as it is, stays effective and contributes to the overall texture. And boy, those chunky drop-shadow credits never fail to make me smile. My Cousin Vinny is deeply defined by the early ‘90s, but it isn’t trapped there.

This is a film that feels as fresh and fun as it did the day it premiered.

My Cousin Vinny manages to walk the line between being culturally specific and emotionally timeless. It’s a relatable story about trying to function in a system that doesn’t seem to have been built for you. It’s about being authentic—and learning to accept help, improve, and trust other voices when you’re in over your head. The film never grandstands about those things. It lets them surface cleanly, naturally, and with real narrative power. And it does so with the confidence of a prestige drama, disguised as a lighthearted courtroom comedy.

Categories

Bruce Hall View All

“When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favorite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol' Bruce Hall always says at a time like that: "Have ya paid your dues, Bruce?" "Yes sir, the check is in the mail."