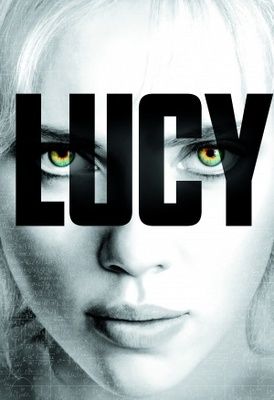

Lucy (2014)

It takes great confidence to open a film on a premise so outlandish that Morgan Freeman is required just to sell it to the audience with a straight face. Lucy is rooted in the long-debunked myth that humans only use ten percent of their brains. But the film serves up the idea as mythological law rather than a scientific fact. We aren’t concerned with accuracy so much as we are momentum. And the real question isn’t even a question, but a fully formed thought exercise:

Suppose we DID only use ten percent of our brains?

What would happen if someone COULD use a hundred?

And, also, she was REALLY hot?

I’m listening…

To make that simple, silly idea land, the film needs an anchor—someone who can start from a place of believability and carry the audience across increasingly heightened terrain. Scarlett Johansson, playing a character who begins the story nearly comical in her lack of awareness, provides that ballast. The emotional transition she delivers—from ingenue to metahuman—is credibly polished. That sincerity is what allows Lucy to work on its own terms. For all its genre excess and speculative leaps, it never winks at its own premise. Luc Besson’s direction—and Johansson’s performance—treat the material with candor, without resorting to camp.

At the outset, Lucy’s ignorance leads to her getting mixed up with a shadowy gang of smugglers, who are transporting an experimental cognitive enhancement drug. Lucy is accidentally exposed to a massive dose, which begins to affect her almost immediately. As her transformation begins, we’re asked to believe not just in her powers, but in the emotional detachment and moral estrangement that follow. That arc could easily collapse under its own weight, but Johansson brings just enough clarity and realism to keep the stakes meaningful.

She also brings guns…

As Lucy’s abductors attempt to hunt her down, she becomes faster, smarter, more powerful—and less human. The tone swings between philosophical action thriller and stylized genre exercise, but Johansson adapts to that dissonance. Her choices carry a kind of grace, even when the film itself becomes more chaotic and symbolic. You don’t get the idea she’s ruthlessly murdering people so much as you get the idea she’s efficiently completing a series of tasks.

Johansson was never groomed as a conventional romantic lead, despite early roles in offbeat dramas like Lost in Translation and Girl with a Pearl Earring. And in action work like this, she tends to occupy a space that’s slightly removed from typical genre expectations: quieter, more internal, less reliant on bravado. With her soft, youthful features and capacity for layered emotion, her work here adds agency in places where the script leans into concept.

Lucy can see radio waves. What can YOU do?

Functionally, Lucy echoes The Fifth Element, another Besson film built around a female character of unremarkable origin and great potential. Both stories follow a woman who begins the narrative in awe, and ends it kind of awesome. Both feature male characters who accompany the lead but do not shape the journey. Freeman, playing a professor with insight into Lucy’s condition, offers running philosophical commentary rather than direct action. Meanwhile, a French police officer (Amr Waked)—introduced as an ally—spends much of the film in a state of stunned observation, swept along by forces he lacks the power to influence or even fully understand.

Kind of like this guy…

Despite Lucy’s conceptual sweep, there are moments of grounded logic that help preserve a sense of continuity. A brief scene in which Lucy eats and drinks in large quantities suggests the biological toll of her transformation. Even in a story where reality is increasingly bendable, there’s a quiet acknowledgment that certain physical laws still apply. The film doesn’t overexplain—it simply shows us the cost of change and moves on. It’s a small but effective gesture that contributes to the believability of the world.

As the story progresses, Besson shifts the visual language: editing sharpens, colors intensify, and the imagery becomes more expressive. As dialogue fades, the film relies more on rhythm and composition to chart Lucy’s metamorphosis. The tension moves beyond survival, toward something much more existential—recalling, in its final minutes, the visual logic of 2001: A Space Odyssey, where image and tempo suggest truths too large for dialogue to contain. Lucy certainly doesn’t aim for (or achieve) that film’s philosophical weight, but it borrows its structure: a transformation depicted not through plot, but through form.

That said, Lucy isn’t without its limitations. Its emotional throughlines are thinner than they could be, and its conceptual leaps may test the patience of viewers expecting something more grounded. And Besson’s habit of fetishizing his female leads into messianic archetypes won’t be for everyone. But there’s something admirable about his film’s conviction. Lucy doesn’t hedge, and it takes big swings. It moves forward with clarity and a willingness to follow an idea to its furthest expression.

If Lucy succeeds, it’s because it respects the internal logic of its own world—however fantastical—and delivers a story that, within that framework, holds together. And Johansson is the reason we believe it. She offers not just a mindful performance, but one that grows steadily more composed without ever becoming hollow. This gives the film a center of gravity it might not otherwise have—and ultimately, one that makes it a ride worth taking.

Categories

Bruce Hall View All

“When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favorite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol' Bruce Hall always says at a time like that: "Have ya paid your dues, Bruce?" "Yes sir, the check is in the mail."