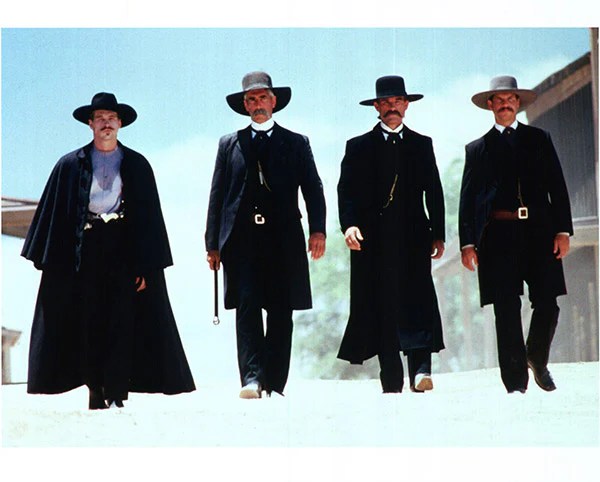

Tombstone (1993)

Highest moustache quotient M(q) of 1993

Val Kilmer’s recent death prompted the kind of reflection we often engage in when someone we admire passes—part tribute, part a way of seeing ourselves more clearly through their work. I’m guilty of this myself, having written a fawning analysis of Kilmer’s autobiography not long ago. And let’s not forget how agog I was over Top Gun: Maverick, where Kilmer’s presence initially seemed purely sentimental—before ultimately proving to be an almost ideal denouement for one of the greatest actors of his generation.

But it’s not just Kilmer’s involvement that makes Tombstone special, and it’s not just his passing that makes it worth revisiting. Few films lean into their myth with as much flair and solemn conviction. On paper, this is a very traditional Western: an already legendary lawman seeks to hang up his guns and live a quiet life of pastoral reflection, only to be reluctantly forced back into a world of unrelenting violence by circumstances beyond his control.

That’s a setup so common among Westerns both good and bad that, if you’ve yet to see it, you might be tempted to overlook Tombstone. But if you did, you’d be wrong to do so. High Noon is an austere film, steeped in moral realism. Shane is a lyrical tragedy full of mournful sentimentality. And Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven is a cold, uncompromising deconstruction of Western myth by one of its most established icons.

“grunting”

But while it explores similar thematic ground as those earlier films, Tombstone emphatically trades realism for ritual, serving up frontier justice not as a dusty period piece, but as an emotional fever dream clad in gleaming gunmetal and gravitas. It fully embraces and enables the larger-than-life aspects of Western folklore—but not to undermine it. Tombstone doesn’t apologize for its flamboyance.

It wants to be the legend.

Fittingly, Tombstone speaks with the voice of screenwriter Kevin Jarre. Originally slated to direct, he was replaced early in production by Kurt Russell George P. Cosmatos. But the script remained Jarre’s, and it’s his tone—formal, elevated, unmistakably mythic—that gives Tombstone its power. Jarre, who also penned Glory, had a knack for stories about duty, masculinity, and sacrifice—all filtered through the lens of history, but anchored in character and conflict. His characters don’t speak like real people; they speak as though they already know they’ll be remembered.

It’s heightened reality, delivered with melodic precision.

Consumptive precision…

The backdrop is the storied town of Tombstone, Arizona, circa 1879. The discovery of silver nearby has attracted all manner of individuals—both well-meaning and self-serving. Most notably, the place has become a preferred haven for a violent gang of outlaws known as The Cowboys, led by the charismatic and ruthless Curly Bill (the incomparable Powers Boothe). Nestled among the law-abiding and the lawless alike, they grow and flourish like a cancer, slowly eating away at the edges of civilized society.

When our heroes walk in on this, their self-assured optimism is able to withstand the decay—at first. But over time, the rot at the heart of the city finds them too, and their drive toward prosperity gives way to pure survival instinct—the only thing truly necessary to exist in Tombstone.

The cast all understand the assignment. Kurt Russell anchors the story as celebrated lawman Wyatt Earp, whose unshakable pragmatism borders on arrogance. He enters Tombstone looking to make his fortune, fully believing he can carve out a profitable life while sidestepping the moral quagmire around him. Sam Elliott and Bill Paxton provide moral clarity and emotional warmth as brothers Virgil and Morgan Earp. Val Kilmer nearly steals the story as the fatalistic Doc Holliday—an old (and morally flexible) friend of the Earps whose wild lifestyle threatens to be his undoing.

And then there’s Michael Biehn, who imbues the legendary Johnny Ringo with a haunting intelligence and an implied backstory so palpable, you feel it rather than hear it. His eyes do most of the talking, and they tell a story far longer than his screen time allows.

“…”

Tombstone isn’t subtle about its tropes. It proudly features multiple rain-drenched reckonings, gleaming silver badges that override both jurisdiction and morality, and women who run breathlessly into the arms of their men as the dust clears. It’s a film that checks every box of Western tradition—but it does so with a moving, almost fanciful sincerity. In many ways, it plays like an ode to the most romantic parts of Western lore: brotherhood, loyalty, and the ache of unfinished reckonings.

Even when it stumbles into sentimentality, the film’s deeper emotional truths remain intact.

Every genre, over time, turns a critical or introspective eye on itself, and Westerns are no exception (see: Unforgiven). But Tombstone is not interested in any of that. It isn’t a deconstruction of the Western, and it wastes no time examining the actual harsh realities of the period. This is a celebration—eager to show us what it might have looked like if the myth were real. And yet, it’s also a meditation, however stylized, on what it costs to live long enough to become a legend. It’s not always accurate, and it doesn’t want to be. It wants to feel right. It wants to feel pure.

And in that mission, it more than succeeds. At its heart is Kilmer, who is and always will be… my huckleberry.

Categories

Bruce Hall View All

“When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favorite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol' Bruce Hall always says at a time like that: "Have ya paid your dues, Bruce?" "Yes sir, the check is in the mail."