To Live and Die in L.A. (1985)

When I was a child, To Live and Die in L.A. was a catchy, oddly complex song by the guys who did that “Everybody Wang Chung Tonight” song. I wasn’t into New Wave, so I clocked it as an interesting choice and moved on. It was only much later, when I became interested in film, that I understood the song to be part of a soundtrack. And it was even later on, after watching enough movies to develop a critical eye, that I discovered the work of the late William Friedkin.

The best way for me to describe my feelings on Friedkin as a director is to say that The Exorcist, The French Connection, and Sorcerer are three of my favorite films of the 1970s, and they’re all also movies that I have no desire to watch again for a very, very long time. The worlds Friedkin creates are cynical places, rife with suspicion against institutions and unwilling to be seduced by the myths of nobility or justice. He was a purveyor of stark realism, eager to lure you with the idea you’re simply going to “watch a movie,” then trapping you for two hours in a crucible of anxious contemplation, as starkly unsettling as holding a mirror up to a mirror.

To Live and Die in L.A. is one of the most uncompromising crime thrillers ever made—a relentless dive into institutional decay, moral erosion, and the kinds of choices that leave no one clean. It’s a gritty story that refuses comfort or convention, favoring immersion over clarity and consequence over catharsis.

The film opens with an extended cold open—a military-style title card announcing the date and time, and that song—the one I had no idea was from a movie. Hearing it in its proper context gives it new meaning as it ushers in a tense setup that ends with a shocking crime committed in one of the last places you’d expect. Only after this does the movie announce itself with splashy, period-appropriate title cards that all but announce:

“If you’re not ready for this, get out now.”

That same ethos permeates every frame that follows.

Released in 1985 and based on the novel by former Secret Service agent Gerald Petievich, To Live and Die in L.A. tells the story of a law enforcement officer whose passion for duty—and the sudden, devastating loss of a longtime partner—blur into a singular, dangerous vision driven by obsession and revenge.

In what should have been a star-making performance, William Petersen plays Richard Chance, a reckless, thrill-chasing agent barely distinguishable from the criminals he hunts. When his partner is murdered, Chance doesn’t just take it personally—he takes it as a license. What follows is a downward spiral of hubris, desperation, and moral obliteration as Chance drags his by-the-book new partner, Vukovich (John Pankow), into increasingly dangerous territory.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…

Petersen is electric in the role, alive with swagger and intensity, embodying the kind of man who believes he’s on the right side simply because he wears a badge. It’s easy to believe him at first—and that’s a credit to Petersen as much as anything. But as the film unfolds, it becomes clear that whatever shreds of devotion to duty Chance was clinging to have long since given way to undisguised bloodlust.

To be fair, Chance has every reason to feel the way he does. His adversary is the kind of brightly burning criminal maniac who can’t help but sear everything he touches into a carbon copy of himself—and he also happens to be responsible for the murder of Chance’s partner.

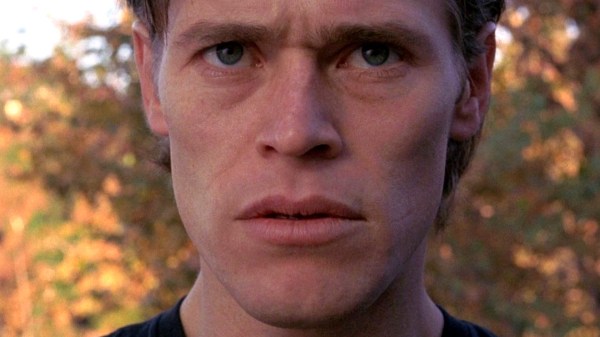

Rick Masters (a baby-faced Willem Dafoe) is a skilled artist turned counterfeiter. He’s managed to transmute his talent in one field—where reward is not based on merit—into another, where the results are more easily quantified. He produces flawless work and is, therefore, able to dictate the limits of his power. He’s no fool, though; Masters is mesmerizing, stylish, and calm when getting what he wants. But the potential consequences are far too high for him to make mistakes—or to let anyone he interacts with become one.

I WILL HAVE SEX WITH YOUR SOUL

Dafoe plays Masters not as a thug but as a conscientious artist—not unlike the Joker, but without the spontaneous outbursts of paralyzing laughter. It’s his principles that make him terrifying. He stands in direct contrast to Chance, whose erosion of standards makes him as much a threat to the criminal justice system as he is to actual criminals.

Friedkin’s world is deliberately inhospitable. The exaggerated color palette—slightly askew from reality—casts L.A. as a sun-scorched purgatory, full of heat and tension but almost no relief. Robby Müller’s cinematography gives it all a dreamlike, hallucinatory quality as if moral decay has leaked into the very atmosphere.

Wang Chung’s synth-heavy soundtrack can’t help but feel of its era, but within the context of the film, it not only works, but feels essential. The compositions are simple but never simplistic, marrying pop sensibilities with an undercurrent of unease that perfectly matches the film’s rhythm and tone.

I can’t imagine this movie without it.

What makes To Live and Die in L.A. so striking is how well it’s made and how little it cares about reassuring its audience. There is no arc of justice, moral victories, or clear lines between good and evil. In many ways, it feels like a thematic cousin to Friedkin’s earlier masterpiece, The French Connection—but far more torrid and considerably more embittered.

To Live and Die in L.A. is not a comforting or hopeful story and spoiler alert—it won’t leave you with a smile on your face. It is, however, true: true to its world, to its characters, and to its own unflinching vision. It’s a film that doesn’t just stay with you—it follows you like heat off the pavement. This is one of the great unsung crime thrillers of its era, and I’m not afraid to say I feel personally responsible, to some extent, for not having seen it sooner.

Forgive me, Mr. Friedkin—and may you find the peace you so rarely granted anyone on screen.

Categories

Bruce Hall View All

“When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favorite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol' Bruce Hall always says at a time like that: "Have ya paid your dues, Bruce?" "Yes sir, the check is in the mail."