The Conversation (1974)

When Gene Hackman died, I set out to watch as many of his best films as possible, with the idea of writing a proper career retrospective. I gave up on that plan pretty quickly—turns out the man made a lot of movies. And too many of them are so good that narrowing them down into a single, readable article—one that wouldn’t require you to eat in between sections—proved impossible.

So instead, I went with the one that stuck with me the most.

The Conversation remains one of the most quietly devastating portraits of personal paranoia ever put to screen. Featuring a masterfully subdued performance by Gene Hackman as surveillance expert Harry Caul, the film is a taut psychological thriller and a meditation on privacy, guilt, and the lies we tell ourselves to feel in control.

The Conversation is Coppola’s follow-up to The Godfather, a legendary film that needs no introduction. Its massive success gave him the freedom to take creative risks, and that freedom pays off in spades. With it, Coppola crafts a film that’s less about grand gestures and more about quiet disorientation—something made immediately apparent right from the start.

The film opens, with credits still rolling, on an eerie overhead view of a crowded San Francisco plaza, overlaid with jagged bursts of electronic interference and muffled city noise. It’s unclear who or what we’re meant to follow, which most viewers will find immediately unsettling. This slow drift toward clarity mirrors the film’s structure, where fragments accumulate meaning only gradually, and perception proves unreliable—for the characters and the audience alike. Even before Hackman’s character appears, we’re immersed in the unnerving experience of watching without understanding. That lack of an emotional foothold isn’t accidental—it’s the first step in a story about the danger of mistaking information for truth and relying on bias for validation.

Now…where did I leave that Golden Globe…?

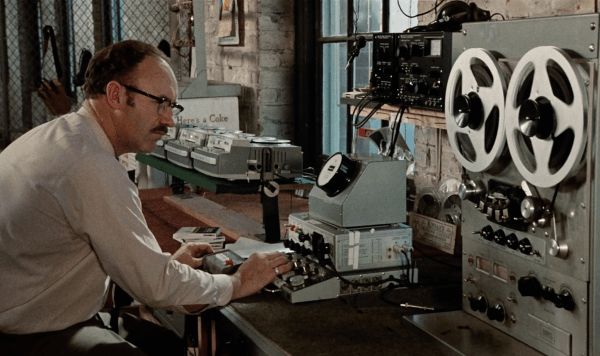

Caul is introduced as a meticulous, secretive professional, part of a loose subculture of phone phreakers, wiretappers, and DIY electronics enthusiasts who operate just outside legal and ethical boundaries. He and his partner Stanley (John Cazale) are freelance surveillance specialists whose trade involves collecting information on unsuspecting targets for shadowy clients whose motives are rarely transparent.

After capturing a conversation between a young couple (Cindy Williams and Frederic Forrest) in the plaza, Caul discovers that a key portion of the audio is obscured. The rest of the recording hinges on this missing segment, and its absence gnaws at him. It becomes clear the couple knew they were being watched and had chosen their location and tactics accordingly—a realization that shifts Caul’s professional detachment into personal obsession. His client seems satisfied with the incomplete recording, but Caul is not. He refuses to hand it over, citing vague concerns about context. In truth, he suspects that everyone else involved—the couple and the client alike—knows something he doesn’t.

“I love your little button nose…”

“I accept your hairpiece…”

The professional control he prides himself on begins to slip, throwing him off balance.

Caul’s reputation is built on a past job with tragic consequences—an outcome he insists he couldn’t have predicted. Yet it’s that very job that earned him the admiration of his peers, a fact that seems to trouble him more than he’s willing to acknowledge. The film invites skepticism, particularly through the eyes of his colleagues, who find it hard to believe that someone with Caul’s expertise wouldn’t have anticipated the potential impact of his work. His insistence on moral distance falters under scrutiny, exposing a deeper discomfort with the gap between his technical skill and the real-world harm it might enable. As the story unfolds, Caul’s behavior grows increasingly erratic, and the very traits that once defined his excellence—his secrecy, his suspicion, his obsessive attention to detail—begin to isolate him, first from his trusted partner, then from the wider professional community that once revered him.

Sometimes, control means hanging out by the throne with a tape player

Caul’s religious beliefs surface throughout the film as a source of guilt, but this rings hollow. He uses faith less as a moral compass than as a shield against the ethical ambiguity of his work. He’s comfortable invading privacy yet increasingly brittle when faced with the consequences. The missing audio becomes less of a professional concern than a personal one. Having built his career on the illusion of detachment, Caul finds he can no longer sustain it. He’s not just trying to complete a job—he’s chasing a hazy possibility, grasping for relevance and control he’s already lost.

The film’s final act cleverly repositions the power dynamics we’ve come to accept so far. Caul’s confidence is shattered when he begins to suspect he’s no longer the observer but the observed. Revelations from earlier in the film, particularly those shared in passing by colleagues, take on chilling new resonance. Clues he might have once caught now pass him by, buried under mounting paranoia. Ultimately, he turns his scrutiny inward, frantically searching for something that may or may not be there. The result is a final moment of self-destruction that is as symbolic as it is tragic.

This is not that moment, but still…

The film closes on a note of quiet devastation, offering a final image that lingers as both a character study and a metaphor. Caul’s obsession, guilt, and refusal to confront his work’s deeper implications leave him unmoored. What remains is the impression of a man consumed by the very thing he once believed he could control. The Conversation doesn’t conclude so much as it dissipates—its final moments are haunted by a sense of inevitability and the lingering question of what becomes of someone who sees too much yet understands too little.

Positioned between The Godfather and The Godfather Part II, The Conversation is sometimes overlooked in Coppola’s filmography—a quieter film overshadowed by two of the most celebrated epics in cinema history. But it deserves to be revisited and remembered as another high point of 1970s American filmmaking: restrained, precise, and devastating in its implications. Few films capture the erosion of certainty with such quiet intensity. Fewer still make that uncertainty feel so well earned.

Categories

Bruce Hall View All

“When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favorite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol' Bruce Hall always says at a time like that: "Have ya paid your dues, Bruce?" "Yes sir, the check is in the mail."